|

SUMMARY The ambition of countries for mitigation action and support has to increase. This is the clear message of countless reports and analyses shared during the 2018 Talanoa Dialogue that has taken stock of collective progress towards the objectives of the Paris Agreement. The Paris Agreement's answer to this need for more climate action is its ‘ambition mechanism’ which obliges countries to consider the outputs of the global stocktake every five years when they review their own ambition level. This policy brief looks at how countries are preparing to enable the ambition mechanism and suggests measures both at national and international level that are key to making it work. POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS For the national (regional for the EU) level the following measures are suggested:

For the international level the following steps are suggested:

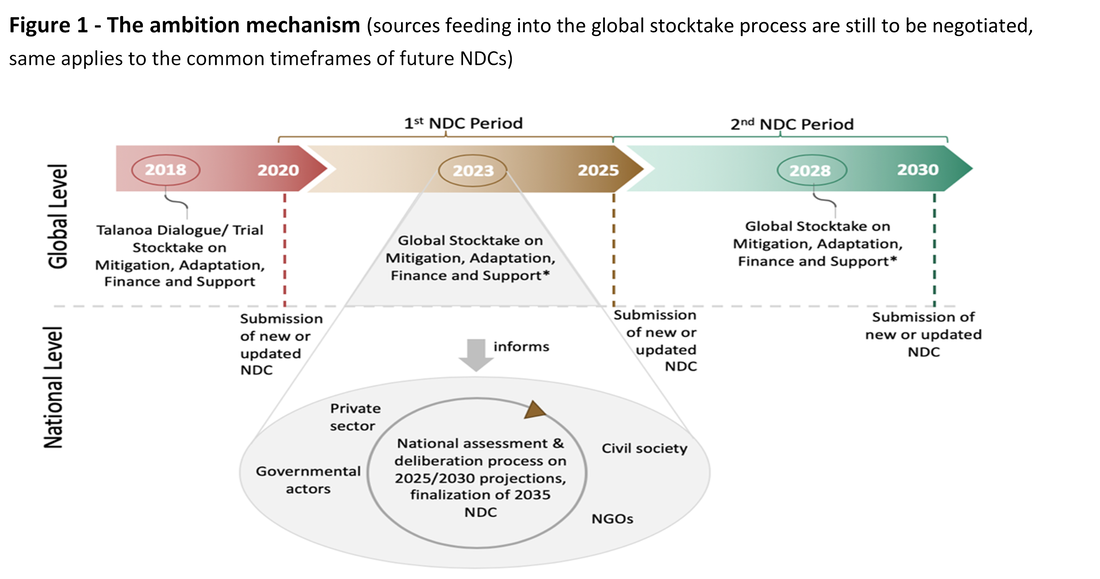

INTRODUCTION Many consider the so called ‘ambition mechanism’ of the Paris Agreement (PA) an essential part of its design with the potential to ensure successively more ambitious action by countries, and thereby achieving its objectives. This mechanism (see figure 1) consists of a global stocktake every five years, starting in 2023, where countries will assess “collective progress towards achieving the purpose of [the PA] and its long-term goal” (Article 14.1). The outcome of the global stocktake “shall inform” (Article 14.3) subsequent Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that also have to represent the highest possible ambition and be more ambitious than the previous NDC in terms of action and support. The core idea of the ambition mechanism is that every country shall reflect on the outcome of the global stocktake and use this as input to enhance their level of ambition if the stocktake shows this is necessary.1 This can take the formal route of revising upwards their NDC, or the informal route of simply galvanizing national action (among governmental actors, civil society, businesses etc.) in the short term. The ambition mechanism was a creative invention of the negotiators of the PA - now it is up to countries to show how it could work. TESTING THE AMBITION MECHANISM - THE TALANOA DIALOGUE The Talanoa Dialogue taking place in 2018 is somewhat of a trial run of the global stocktake. Its objective is to take stock of collective progress towards the long-term goal of the PA and encourage enhanced ambition among countries.2 It aims to do so by conducting a dialogue based on story-telling for creating empathy and trust. It was launched in January 2018 with a preparatory phase in which all actors were invited to hold Talanoa Dialogues in their own context and submit input to the global dialogue. All input, as well as the outcome of the IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C that came out in October 2018, provides the basis for the political phase taking place at the 24th Conference of the Parties (COP24) in Poland on 11 December.3 While the political outcome is what countries are expected to take home and reflect on, the way countries have engaged with the Talanoa process can still provide some insights into how countries are starting to engage with the ambition mechanism. Our analysis shows that 44 of the 184 Parties to the PA made submissions to the Talanoa Dialogue portal and governments organised 37 Talanoa Dialogues either at regional or national level.4 These sessions included story-telling and showcasing of best practices. They were mostly organised as one day multi-stakeholder dialogues and not linked to national/regional policy processes. The exception here is Peru, which designed a three-month long public deliberation process throughout the country including stakeholders from the private sector, NGOs, civil society, indigenous communities, academics and public institutions.5 The national dialogue was organized by the Peruvian Ministry of Environment with the aim to develop the regulations of the framework climate legislation. INSPIRING EXAMPLES OF NATIONAL ACTIONS FOR ALIGNMENT Very little is known about what the processes through which countries have developed their NDCs look like, what they plan to do with the Talanoa Dialogue outcome or how they plan to reflect on the outcome of future global stocktakes and let their NDCs ‘be informed’ thereby. Our research is an effort to start filling this gap. We particularly looked for countries that seemed to be ahead of the curve and that could serve as ‘best practice’ in preparing their institutional framework for the PA’s ambition mechanism. We share the stories of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Mexico and the European Union that can inspire others. These three stories illustrate how both existing legislation can be adapted or new legislation adopted to enable the ambition mechanism. 1: Republic of the Marshall Islands This vulnerable Small Island Developing State actively pushes for more ambitious pledges by Parties, which is reflected in its active role in the High Ambition Coalition. The Republic of the Marshall Islands was the first country to communicate an updated NDC to the UNFCCC in November 2018 with an enhanced 2030 target of 45% emissions reduction below 2010 levels.6 The Republic of the Marshall Islands adopted its long-term low GHG emission development strategy, the Tile Til Eo (‘Lightening the way’) climate strategy, in September 2018, which outlines a pathway to zero emissions by 2050.7 It formalizes a national ambition mechanism by requiring a review of the long-term strategy at least every five years. This revision process also includes the recommendation of new targets for subsequent NDCs which has to take place one year ahead of its NDC submission to the UNFCCC. For this purpose, a domestic process will be established to monitor its implementation and to ensure effective review and update processes. 2: Mexico Mexico, one of the first countries with a framework climate legislation as of 2012, can be considered a front-runner in the formalization of the PA’s ambition mechanism. Mexico took an important step towards the alignment of national and international policy processes in July 2018 through the adoption of a Decree to update the General Law on Climate Change. The updating process aimed at fully capturing the provisions of the PA and the targets of Mexico’s NDC. Article 63 of the amended law anchors the NDC development in its climate legislation.8 It determines that the inter-ministerial Commission on Climate Change (CICC) has to propose and approve the adjustments or modifications to scenarios, trajectories, actions and goals in its National Strategy on Climate Change (ENCC) and its NDC in accordance with its five-year review cycle. The Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources together with the CICC should revise the NDC in line with the PA and the decisions which emerge from it. The same review process applies to the National Climate Change Strategy at least once every ten years regarding mitigation policy and every six years regarding adaptation policy. Importantly, Article 98 of the amended law states that the national climate change policy will be subject to periodic and systemic evaluation which will take the IPCC reports and the periodic evaluations established within the PA into account. This evaluation process might then result in a proposal to modify, amend or totally reorient the national climate change policy. Mexico’s climate law incorporates the various national instruments under one overarching framework. The Special Program on Climate Change (PECC) constitutes the short-term guidance for actions to be undertaken at the federal level in line with the ENCC. The next PECC will cover the period 2019-2024. In 2016, Mexico also communicated its long-term strategy, the so-called Mid-Century Strategy (MCS), which emerges from its ENCC (2013) and foresees a reduction of 50% of national GHGs by 2050 below 2000 levels.9 The strategy makes some links to the international level as it states that Mexico is committed to update its long-term strategy according to the provisions agreed under the UNFCCC. In case of a revision of the MCS this shall be communicated to the UNFCCC to make sure that this information can be considered in the global stocktake process. 3: The European Union (EU) The EU will establish its own mechanism to close ambition gaps at a regional level through the adoption of the Regulation on the Governance of the Energy Union in December 2018.10 This regional ambition mechanism builds upon Member States’ (MS) submissions of long-term strategies with a mid-century perspective and so-called integrated national energy and climate plans covering ten-year periods starting in 2021 to 2030. By 31 December 2019, MS need to submit their final national plans, after draft plans have undergone an assessment by the Commission. In this assessment, the Commission compares the collective efforts communicated by MS in their bottom-up national plans against the Union’s 2030 targets for energy and climate which impose a 40% cut in GHG emissions compared to 1990 levels, a share of renewable energy of at least 32% and an improvement of energy efficiency of at least 32.5%. The Commission can express country-specific recommendations for the final energy and climate plans in case a MS does not live up to its commitments. Article 38 of the Regulation links and aligns the EU ambition mechanism with Article 14 of the PA.11 The article states that the results of the global stocktake shall inform the review of the Regulation. Within six months of each global stocktake, the Commission has to report to the European Parliament and to the Council on the operation of the Regulation and may suggest proposals to ensure its effective implementation. The revision of the Regulation is adjusted to the global stocktake’s five-year cycle. The updating process of national energy and climate plans, which should only undertake modifications to reflect increased overall ambition, is supposed to take place by 30 June 2024 and every ten years thereafter, thus right between the global stocktake and the due date for new NDCs. The outcomes of the 2028 global stocktake could then be considered in the preparation of the second national plans whose drafts are due by 1 January 2029. The EU’s NDC ambition level is fixed by the ETS Directive and the Effort Sharing Regulation (non-ETS sectors).12 The revised EU ETS Directive (04/2018) specifies that in the context of each global stocktake, the provisions of the Directive will be kept under review. The Effort Sharing Regulation, adopted in May 2018, determines that its review in 2024 and every five years thereafter can be informed by the global stocktake. On 28 November, the European Commission announced its long-term strategic vision to achieve netzero GHG emissions by 2050.13 The vision includes two net-zero emissions scenarios by 2050, but policy proposals to achieve this vision have not yet been developed. There is a possibility that EU 2030 level ambitions could also be enhanced as a result of this and of the outcome of the Talanoa Dialogue through a revised NDC by 2020. CREATING A LEARNING COMMUNITY Countries are not comfortable holding each other individually to account for living up to obligations under the Paris Agreement except through mutual encouragement and support. This is why the Committee of Implementation and Compliance (Article 15) is explicitly facilitative in nature excluding any form of sanctions.14 It follows that the only link between the collective accountability mechanism - the global stocktake - and individual state accountability is how seriously countries take the obligation to reflect on the outcome of the global stocktake and enable this to inspire higher level of ambition. Considering the urgency to step up ambition it is not wise to wait patiently for a few rounds of 5-year stocktake cycles with some ad hoc experimentation by countries in how to make the ambition mechanism work. Rather, learning needs to happen fast on questions such as:

Countries have to learn fast. This is best done with approaches rooted in the legal, administrative and cultural traditions of a country yet being open to learning from inspiring neighbours from far and wide. Helpful for this learning process would be if countries in their NDCs described the process through which they were developed including how the outcome of the global stocktake was considered.15 Cross-country learning can be further supported by international institutions and underpinned with solid data collection from the research community. Endnotes

1 UNEP (2017). The Emissions Gap Report 2017. United Nationa Environment Programme (UNEP), Nairobi. 2 UNFCCC (2017). Draft decision 1/CP.23. Conference of the Parties, Bonn. 3 For an overview of all the inputs received during the Dialogue’s preparatory phase, see the analysis provided by the UNFCCC Secretariat: https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/9fc76f74-a749-4eec-9a065907e013dbc9/downloads/1ct8fja1t_768448.pdf 4 Non-party actors submitted 429 contributions to the portals and organised many additional events. 5 For more details on the Peruvian Talanoa Dialogue see http://www.minam.gob.pe/cambioclimatico/ dialoguemos-reglamento-lmcc/ 6 RMI (2018). The Republic of the Marshall Islands Nationally Determined Contribution. 7 RMI (2018). Tile Til Eo 2050 Climate Strategy “Lightening the way”. 8 DOF 13/07/2018. Decreto por el que se reforman y adicionan diversas disposiciones de la Ley General de Cambio Climático, Mexico City. 9 SEMARNAT-INECC. (2016). Mexico’s Climate Change Mid-Century Strategy. Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) and National Institute of Ecology and Climate Change (INECC), Mexico City. 10 Council of the European Union (2018). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council on the Governance of the Energy Union, Brussels. 11 Council of the European Union (2018). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council on the Governance of the Energy Union, Brussels. 12 EU (2018). Directive (EU) 2018/410 of the European Parliament and the Council of 14 March 2018 amending Directive 2003/87/EC, Brussels. 13 European Commission. (2018). A Clean Planet for all: A European strategic long-term vision for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate neutral economy, COM(2018) 773 final, Brussels. 14 This means that in common with so many international environmental agreements there is no room for ‘enforcing compliance’ at the international level. The national level is where enforcement has to happen - coming out of formal or informal accountability mechanisms, see Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen SI et al. (2018) Entry into force and then? The Paris agreement and state accountability. Climate Policy 18 (5): 593-599. 15 The Environmental Integrity Group (EIG) has made proposals for this in the negotiations on the rule book for the Paris Agreement, see Republic of Korea on behalf of EIG (2017) EIG Submission on Matters Relating to the Global Stocktake Referred to in Article 14 of the Paris Agreement, available at https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/submissionsstaging/Pages/Home.aspx. Based on an analysis of NDCs already submitted with the help of the NDC Explorer (see https://klimalog.die-gdi.de/ndc/), it is clear that only a very limited number of countries addressed the link between international and national review processes and it was not possible to determine if those who did actually considered the global stocktake as formulations were vague.

7 Comments

|

AuthorS

Sylvia Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen and Juliana Kessler ArchivesCategories |

|

The One World Trust is a registered charity.

English Charity number. 1134438 Read our privacy policy here |

Contact us

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed